The Locust Fork River, Tributary to Black Warrior River. Photo Credit: Ginger Perkins, Friends of the Locust Fork River Photo Contest.

Written By: Laura Cooley, Rachel McGuire, Emily Ward, and Sydney Zinner

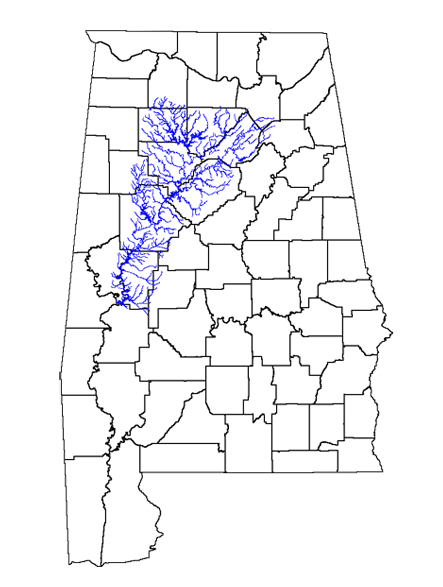

The Black Warrior River, the primary tributary of the Tombigbee River, is seated in West Central Alabama and spans 178 miles across the state. (Figure 1). It is the largest river system contained entirely within AL state lines and drains an area of 6,275 square miles. The upper portion of the Black Warrior River Basin is forested at the southernmost area of the Appalachian Mountains. It borders the Birmingham suburbs in west Alabama and travels south to become forests again, along the Coastal Plain. The main stem of the river is highly impounded, and the reservoirs provide drinking water, hydroelectric power (1), commercial navigation, and industrial process water (4).

Figure 1. Black Warrior River (Map credit: Sydney Zinner)

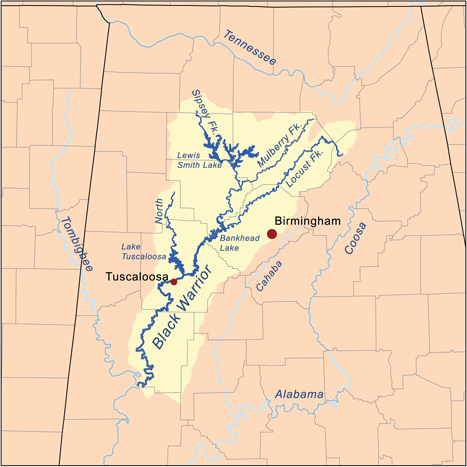

There are 3 main tributaries of the Black Warrior: Mulberry Fork, Locust Fork, and Sipsey Fork (Figure 2). The western most fork, Sipsey, flows into the Mulberry Fork, which is the center prong. They flow together south to meet the right prong, Locust Fork, at the Jefferson and Walker County line.

Figure 2. A map of the Black Warrior River and its 3 main tributaries: Sipsey Fork, Locust Fork, and Mulberry Fork. (Map credit: Kmuuser “Black Warrior River Map”)

History

Figure 3. View of the Black Warrior at a period of high water (1905). Photo Credit: Eugene Allen Smith Collection, Courtesy of The University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections

The Black Warrior River is named after Chief Tushkalusa. The name “Tushkalusa” originates from the Choctaw words “tushka” which means warrior and “lusa” which means “black”. Tushkalusa is known for leading the Battle of Mabila to protect his villiage against the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto. The city of Tuscaloosa, located in the Black Warrior River basin, is also named after him.

The Black Warrior River was very strong in Mississippian culture. Moundville Archeological Park is in the Black Warrior basin. The park was once the site of a prehistoric Native American community. At its peak, it was the largest city in America. The Mississippian people built large “earthen mounds” to serve as platforms for structures and homes (3). This is where they got their name, “Moundbuilders”. (2)

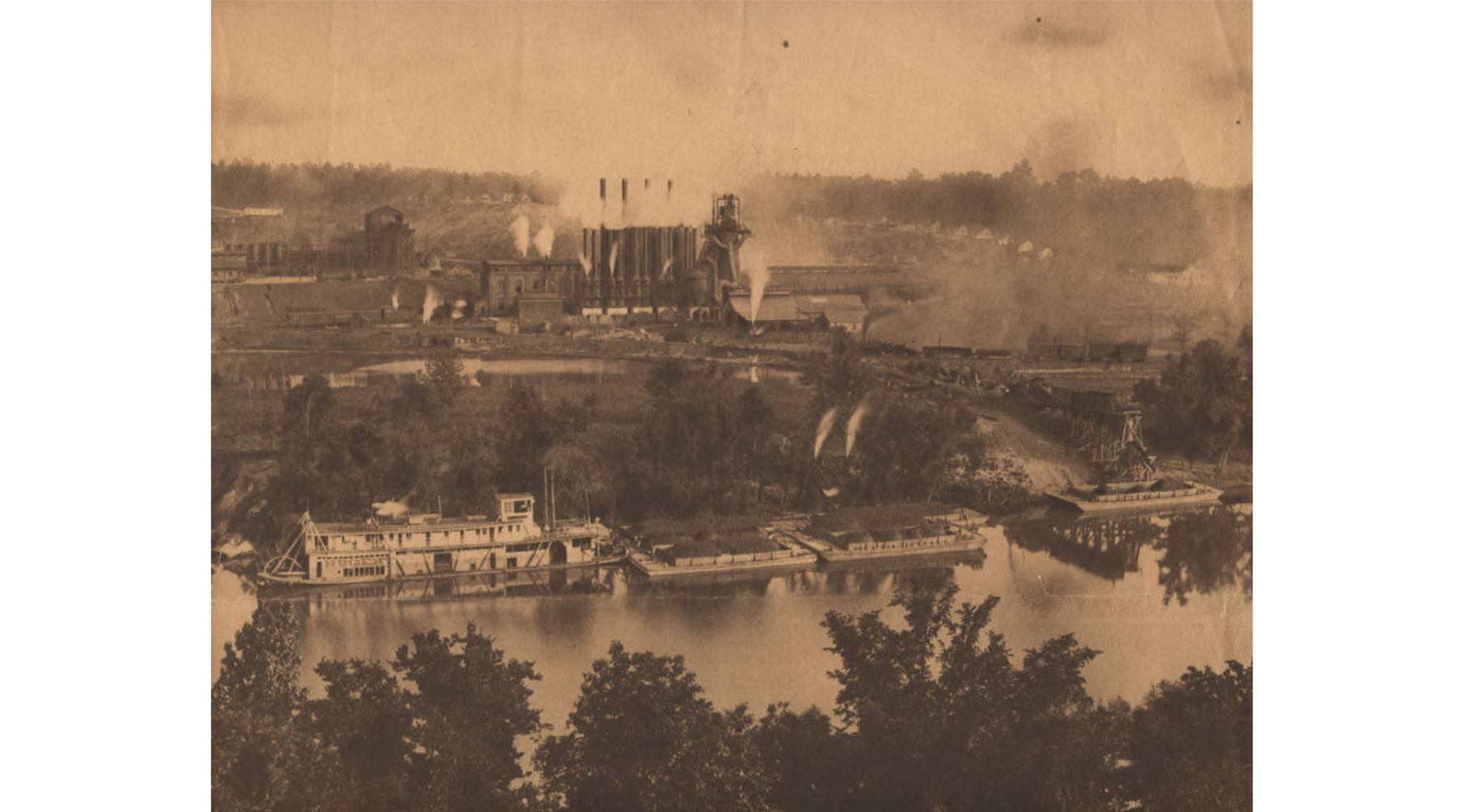

The Black Warrior River has long been used for commercial and industrial shipping in west Alabama. In the 19th century, navigating the river north of Tuscaloosa was difficult due to unpredicted water levels and rocky shoals. This caused coal shortages and led the federal government to build a series of locks and dams above Tuscaloosa. Commerce still suffered after the construction of these because of dry riverbeds during drought. In the 20th century, Alabama Power began construction on Smith Dam on the Sipsey Fork to create a reservoir for an additional source of drinking and industrial water. (5)

The Black Warrior became the first river in Alabama that was significantly modified to improve navigation. Now, nearly 200 miles of the river is navigable for tow boats and their barges. Coal, chemicals, steel, wood, and more are imported and exported through the river. Figure 5 features Coal Barges in Tuscaloosa in 1915.

Figure 5. Loading Coal Barges in Tuscaloosa County for Export at Mobile and New Orleans in 1915. (Photo credit: Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH).)

Figure 6. View of Blue Springs Creek, part of the Locust Fork River. (Photo credit: Dena Waldrop, Friends of the Locust Fork Photo Contest.)

Notable Tributaries

There are three primary tributaries to the Black Warrior River: Mulberry Fork, Locust Fork, and the Sipsey Fork. (See Figure 2 for a map)

Mulberry Fork starts in Northeastern Cullman County, forming a boundary between Cullman and Blount County. The Sipsey Fork joins Mulberry Fork from the northwest approximately 15 mi (24 km) east of Jasper. Mulberry Fork enters Bankhead Lake Reservoir in Walker County.

Mulberry Fork flows through the Warrior Coal field where most Alabama’s coal reserves are located. Mulberry was placed on America’s Most Endangered Rivers 11 list in 2011 and 2013 because of its proximity to the coal mine and the potential threat of the mine’s wastewater polluting the river. One mine in particular lies 800 foot from a large drinking water intake. The Black Warrior River and its tributaries provide drinking water for cities like Birmingham, Bessemer, Cullman, Jasper, Oneonta, and Tuscaloosa.

Locust Fork stretches across Blount, Etowah, Jefferson and Marshall Counties (Figure 6). It is considered, “a relatively undeveloped whitewater stream with cascading waterfalls and beautiful stands of mountain laurel and wild azaleas.”(1). Many consider Locust Fork the best place for whitewater kayaking in Alabama due to its whitewater streams and waterfalls. In Blount County, you will find the river drops over 500 feet which creates up to Class IV rapids. Lost World’s in Alabama’s Rocks states that the Locust Fork is in a physiographic region known as Sand Mountain. This region indicates that Locust Fork flows through a 300-million-year-old ancient riverbed. (6) The ancient riverbed is older than the Appalachian Mountains, cutting through mountains numerous times via features known as “water gaps” (2). The Locust Fork River ranks in the top 2% of the nation’s free flowing rivers with “outstandingly remarkable values” in all seven categories of the Nationwide Rivers Inventory of the National Park Service. Locust Fork has an active stewardship group called Friends of the Locust Fork River. Their website provides more detailed information about volunteer opportunities, whitewater rafting, wildlife, and more.

Sipsey Fork is the largest fork of the Black Warrior River. Sipsey is designated federally as Alabama’s only Wild and Scenic River as part of Public Law 100-57 7. Sipsey Forks headwaters originate within the 24,962-acre Sipsey Wilderness and Bankhead National Forest (2). Brushy Creek is considered the sister river of the Sipsey Fork in the Bankhead National Forest. Brushy is known for its clear waters and scenic views. Brushy Creek flows into the Lewis Smith reservoir, a 35 mile long, 21,200-acre impoundment located in the headwaters of the Black Warrior River. Sipsey is also well known for its rainbow trout that have been stocked monthly since 1974 right below Smith Lake.

Figure 7. Kayakers at the Alabama Cup Races at King’s Bend. (Photo credit: Christopher Verdi, Friends of the Locust Fork River Photo Contest.)

Geography

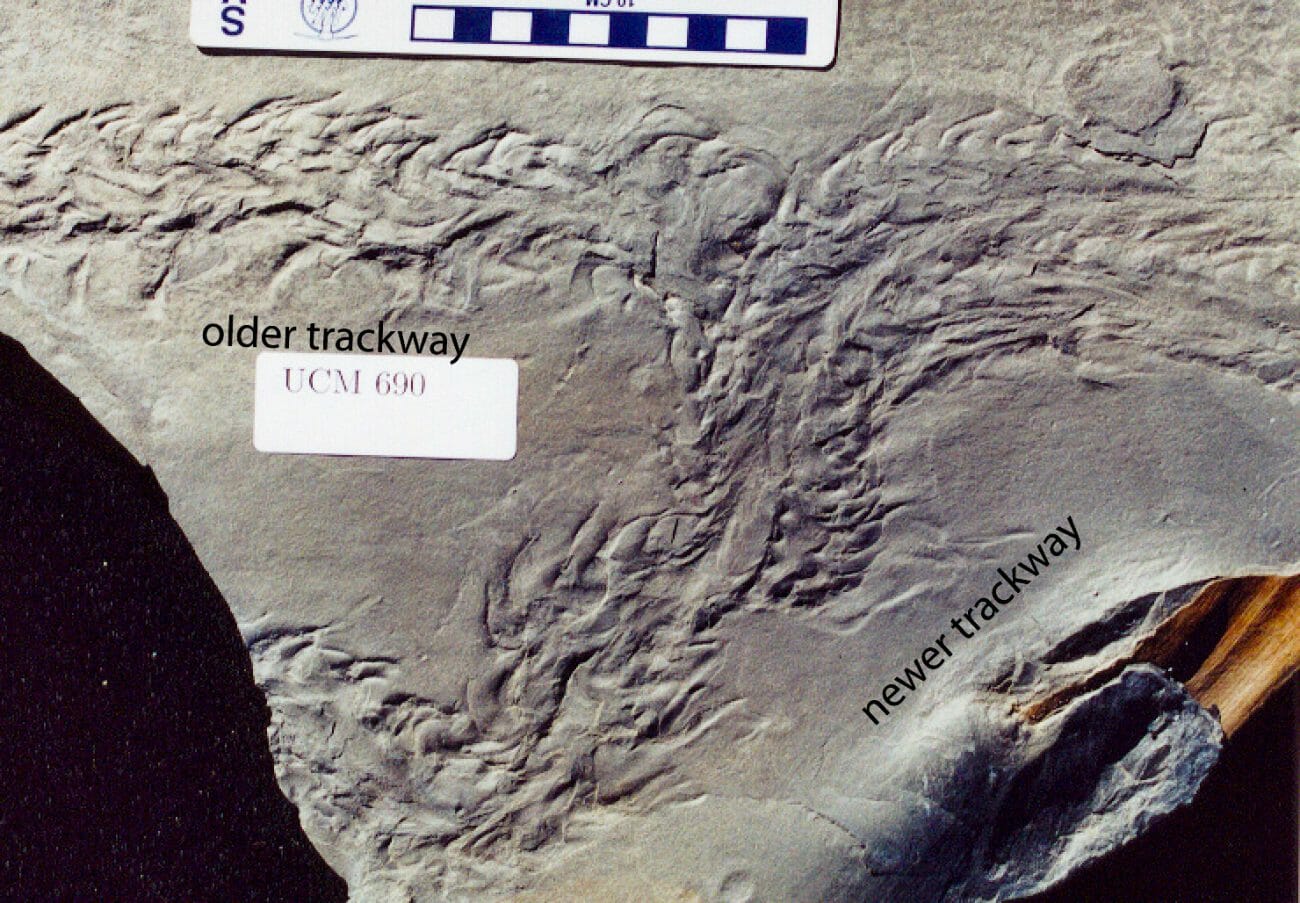

Within the rocks of the Warrior River basin, trace fossils that contain of amphibians, reptiles, and fish tracks were found. The site of these fossils is in Walker County at the Steven C. Minkin Paleozoic Footprint Site. These fossils are the “most prolific source of vertebrate trackways of its age in the world” (Merkel, 2023). The fossil trackways, are preserved in shale that formed from mud on a freshwater tidal flat about 315 million years ago (12)

Figure 8. “A fossilized horseshoe crab trackway crosses over a trackway left by another horseshoe crab that passed by earlier in what was the soft mud of a shallow tidal basin in this section of the Steven C. Minkin Paleozoic Footprint Site. (Courtesy of the Alabama Paleontological Society)

Dams

There are four dams on the main stem of the Black Warrior River.

The John Hollis Bankhead Lock and Dam (Figure 9) forms Bankhead lake. It is the northernmost structure on the mainstem of the Black Warrior and is located in Tuscaloosa County. The original lock was built in 1915 and replaced by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1963. Alabama Power Company constructed and maintains a hydroelectric powerhouse below the lock which they built in 1963. Bankhead is one of two Army Corps owned dams fitted with an Alabama Power Company hydropower generating turbine.

Figure 9. Bankhead Lock and Dam. (Photo credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

Holt Lock and Dam (Figure 10) forms Holt Lake. This was completed by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1969, and like the Bankhead dam, is fitted with Alabama Power Company hydropower turbines. The new dam inundated four older locks, some of which were removed to prevent navigation hazards during low water. Holt Lake extends upstream 19 miles to the John Hollis Bankhead Lock and Dam. The lake covers 3,200 acres. The primary uses for this reservoir are navigation, flood control, and recreation.

Figure 10. Aerial view of Holt Lock and Dam on the Black Warrior River in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama.(Photo credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

William Bacon Oliver Lock and Dam (Figure 11) forms Lake Oliver. It was the first modern improved dam to be built and covered the first three locks built on the Black Warrior. Completed in 1940 the dam is in the city of Tuscaloosa. The original lock was built in 1895.

Figure 11. The William Bacon Oliver Dam spans the Black Warrior River between Tuscaloosa and Northport in Tuscaloosa County, with its lock shown at the left. (Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division via The Encyclopedia of Alabama)

Armistead I. Selden Lock and Dam (Formerly Warrior Lock and Dam) forms Warrior Lake. It sits 6 miles southeast of Eutaw. Warrior Lake extends 77 miles to the William Bacon Oliver Lock and Dam in Tuscaloosa and has a surface area of 7,800 acres. This reservoir is frequently used for water sports and recreational opportunities.

Environment + Wildlife

There are 211 species found in the Black Warrior River Basin. The endangered Black Warrior Waterdog (Figure 12) is only found in the Black Warrior Basin. It is a large, aquatic, nocturnal salamander that retains larval characteristics such as frilly, external gills for its entire life. 8 Other aquatic life includes the 33 species of crayfish, 127 species of freshwater fish, 36 species of mussel, and 15 species of turtle. The Black Warrior River is home to many species of endangered aquatic life as well. There are 4 endangered freshwater fish species: Cahaba shiner, rush darter, vermilion darter, and watercress darter (Figure 14). There are 5 species endangered mussels: dark pigtoe, ovate clubshell, southern clubshell), southern combshell, and triangular kidneyshell. And there is also the endangered plicate rocksnail and the threatened flattened musk turtle (Figure 13) .

Figure 12. Endangered Black Warrior Waterdog. (Photo credit: Joe Jenkins)

Figure 13. Flattened Musk Turtle (Photo credit: Joe Jenkins)

Figure 14. Endangered Watercress Darter (Photo credit: Jeffery Drummond)

Water Quality

The Clean Water Act section 303(d) list contains the state’s impaired and/or threatened waters. In 2024 the 303(d)-list released by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management listed the Black Warrior River and its tributaries 69 times. The impairments are as follows: 15 counts of Metals (Mercury), 4 counts of Nutrients, 1 count of Organic Enrichment (BOD), 34 counts of Pathogens (E. coli), 2 counts of Pesticides (Dieldrin), 6 counts of Siltation, and 7 counts of Total Dissolved Solids. The sources of these impairments are agriculture, animal feeding, aquaculture, atmospheric deposition, collection system failure, municipal, surface mining, unknown sources, urban runoff, and storm sewers. (9)

The Black Warrior Riverkeeper notes, “Most of Alabama’s coal reserves are found in the Warrior Coal Field, which is the source of so much coal mining in the Black Warrior basin over the past 200 years. There are over 50 currently permitted surface or strip mines, mountaintop removal mines, and underground mines. Strip mines can range up to nearly ten thousand acres in size and some of the deepest vertical shaft underground coal mines in America are in Tuscaloosa County. Most of the coal mined here is exported overseas. Coalbed methane hydraulic fracturing occurs at thousands of wells to extract natural gas trapped in coal deposits.” (2).

A copy of a basin level Watershed Management plan can be found here. The publication of this plan was funded by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 104(b) of the Clean Water Act and the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (10).

Organizations related to the Black Warrior River

- View the Alabama Scenic River Trail website for suggested paddle guides on the Black Warrior River.

- Friends of Locust Fork River

- Black Warrior Riverkeeper

References

1 Outdoor Alabama. (2024). Black Warrior. https://www.outdooralabama.com/rivers-and-mobile-delta/black-warrior

2 Black Warrior River Keeper. (2020). River Facts. https://blackwarriorriver.org/river-facts/

3 The University of Alabama. (2024). Moundville Archaeological Park. https://moundville.museums.ua.edu/about/

4 Black Warrior River Keeper. (2020). The River. https://blackwarriorriver.org/the-river/

5 Sznajderman, M. (2008). Lewis Smith Dam and Lake, Encyclopedia of Alabama. https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/lewis-smith-dam-and-lake/

6 Lacefield, J. (2013). Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide to the State’s Ancient Life and Landscapes, Alabama Museum of Natural History, the University of Alabama

7 United States Congress. (1988). Sipsey Wild and Scenic River and Alabama Addition Act of 1988. In Public Law (Vols. 100–547) [Public lands]. https://www.rivers.gov/rivers/sites/rivers/files/2022-10/Public%20Law%20100-547.pdf

8 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Necturus alabamensis FWS.gov. https://www.fws.gov/species/black-warrior-waterdog-necturus-alabamensis

9 Alabama Department of Environmental Management. (2024). Section 303(d) List Clean Water Act. https://adem.alabama.gov/programs/water/wquality/2024AL303dList.pdf